When I was about 14 I discovered that the interwar ‘plotland’ development of Bungalow Town, which had existed on the beach at Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, a few minutes’ walk from my family home, had been deliberately destroyed and overwritten by the local council in the immediate aftermath of World War 2, a story that I later uncovered in more detail through the writings of Dennis Hardy and Colin Ward (2002:91-102).

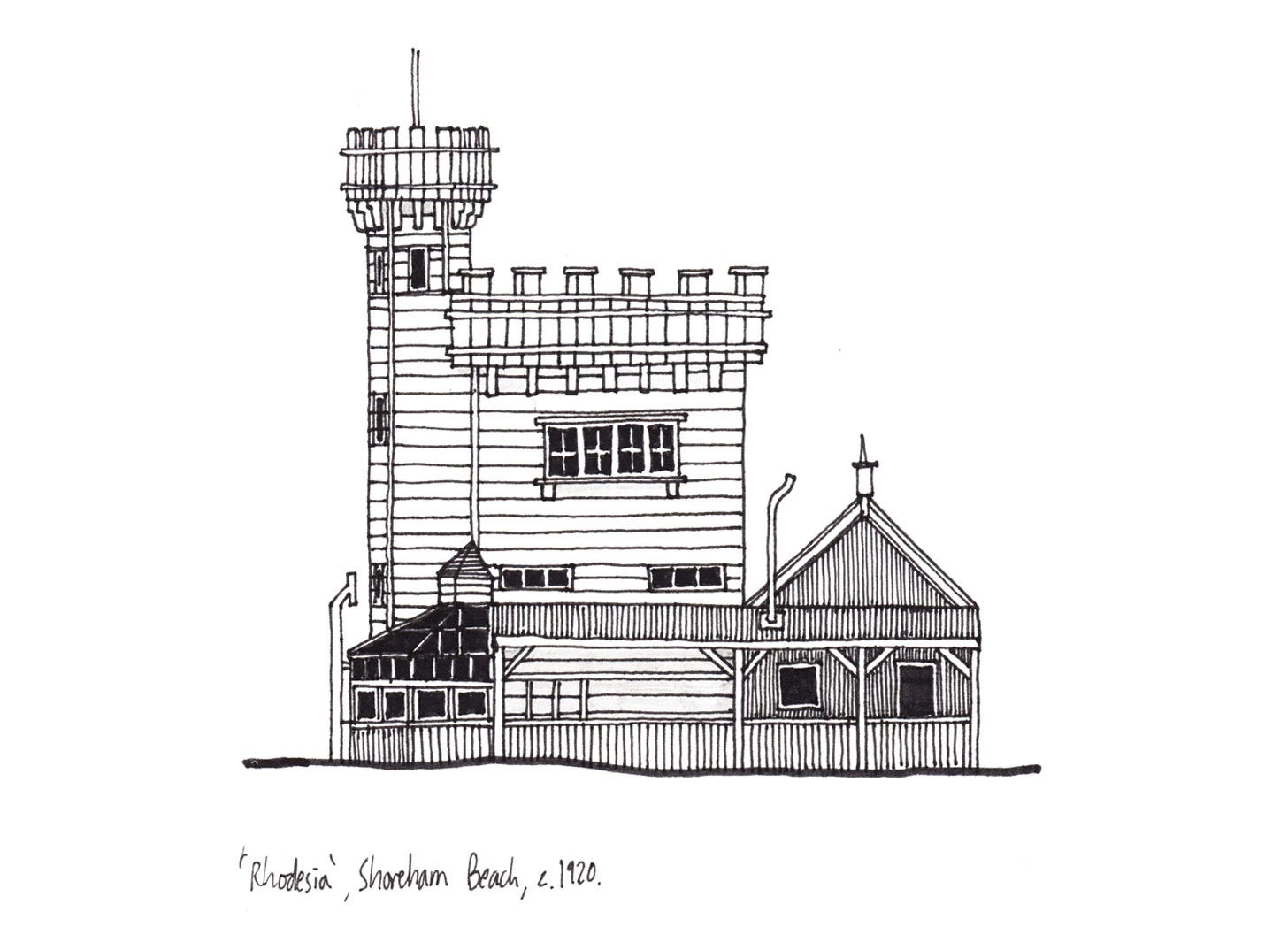

Bungalow Town was my first historical obsession. I was particularly fascinated by the stories of Bungalow Town’s history as a place of early film-making, a time when good quality daylight was needed to shoot. Large glazed film studios appeared on the beach to accommodate the studios, and characterful bungalows, incredibly free in their expression (ranging from exotic, ‘colonial-style’ villas to romantic multi-storey timber castles) appeared to accommodate performers and their entourages.

By my time, all of this was gone, replaced with a decent but unexciting estate of houses, with the very occasional plotland survivor, a railway carriage house or ‘bungalow church’, scattered between them, and occasionally a new house or houseboat which appeared to be working in Bungalow Town’s otherwise vanished tradition.

I didn’t know then that the erasure of Bungalow Town was a paradigmatic moment in the history of town planning in the UK, but the story of Bungalow Town revealed that, in the very familiar context of the town in which I grew up, there had existed in the recent past and in the same space, two radically competing models of development. The former was ad-hoc, piecemeal, often disorganised and incoherent but equally often joyful and imaginative; the latter statutory, paternalistic and concerned with order and propriety. It seemed to me that the postwar model had made a mistake in disregarding, or perhaps deliberately opposing, the efforts of that ‘other’ model. My discoveries on the beach in the remains of Bungalow Town led to an overwhelming interest in the politics of development, in the role of the state in development processes, and the relationship of state practices to popular practices.

The exploration and critique of British statutory planning offered here is done so in the belief that ‘planning’, defined herein as the political tool which we collectively use to decide the future of our environment, is of fundamental importance to addressing the problems of a world facing enormous social, political, cultural and environmental challenges.

Throughout its existence, however, British statutory planning has been characterized by a series of hegemonic structures and apparata - problematic dichotomies of professional vs. amateur, planned vs. unplanned, order vs chaos – which frame the discipline and the system in ways which are fundamentally disconnected from, and oppositional to, the wider popular practices – discourse and construction - in which statutory planning exists. We can see these in the story of Bungalow Town and in multiple other contexts echoing through the decades. The work of Antonio Gramsci and latterly Chantal Mouffe helps us to understand these power structures and is summarised in the text that follows.

I want here to rewind British statutory planning practice back to its roots at the turn of the twentieth century, analysing propositions for it that were made by its progenitors and early advocates. The culture of planning as initiated during that period is revealed to be hegemonic in its character, setting up pervasive but false dichotomies that shaped planning practice in its formative years and which are still present, albeit in an evolved form, in the system we have today. The British statutory planning system is undergoing a period of profound crisis: ideological attack at the scale of national government, severe skills and funding shortages, and a loss of popular faith in its practices and processes. This crisis is taking place within a wider rejection of extant models of representative democracy. This exploration of the power structures at the birth of British planning is therefore offered as a hopefully timely investigation into how we may yet escape ancient traps laid for us by practitioners and theorists of decades past.

Cultural hegemony was first articulated by the Italian political activist and Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) as a way of understanding the means through which power is gained by class groups and, ultimately, how it might be gained by the suppressed. In Gramsci’s thought, the hegemony of a given political class meant that ‘that class had succeeded in persuading the other classes of society to accept its own moral, political and cultural values’ (Joll, 1977: 99) and, furthermore, ‘a successful ruling class is one which before actually obtaining political power has already established its intellectual and moral leadership’ (1977:100). Gramsci’s work established a terrain where cultural production - high or low, art, literature, music - can be understood as having agency within a political system. Building on this, in 1979, Chantal Mouffe widened Gramsci’s positioning of ‘intellectual leaders’ as core to the creation and maintenance of cultural hegemony to include what she terms ‘hegemonic apparatuses: schools, churches, the entire media and even architecture and the name of the streets’ (Mouffe, 1979: 187). It is this notion of the hegemonic apparatus, present in Gramsci but articulated by Mouffe, that enables a reading of planning in hegemonic terms, and ones that understand it as – among other things - a work of culture. Clearly, any state planning system is not in itself a cultural hegemony in entirety, but, following Mouffe, it can function as a hegemonic apparatus within a larger political system, and can fulfill, in part, the wider aims of a dominating class or other elite.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the massive urbanisation of the British population and its concentration into towns and cities was an established fact, as were the social and health issues that accompanied this concentration (Briggs, 1968). A succession of governmental reforms and policies – including successive Public Health Acts - had failed to address the profound issues associated with the industrial city, while philanthropic housing projects in the major cities had led the way in improving working class housing conditions without, of course, solving the underlying problem. These issues, as the century turned, fed into calls for state intervention in the structuring of urban environments (Ashworth, 1954) from non-statutory bodies including the National Housing Reform Council, the Association of Municipal Corporations, the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Surveyors’ Institute and the Association of Municipal and County Engineers (Cullingworth & Nadin, 2006: 16).

This local-level advocacy had its roots in a long tradition of urban reform at that level (1954: 180), but was now coalescing into sustained calls for national legislation in support of town planning, nested within related concerns about the state of housing. These calls led eventually to the Housing, Town Planning, Etc. Act 1909, the first legislation in the UK bearing the term ‘town planning’, the purpose of which, as defined by the president of the Local Government Board which had passed the act, was to:

provide a domestic condition for the people in which their physical health, their morals, their character and their whole social condition can be improved by what we hope to secure in this bill. The bill aims in broad outline at, and hopes to secure, the home healthy, the house beautiful, the town pleasant, the city dignified and the suburb salubrious. (John Burns, President of the Local Government Board, cited in Cullingworth & Nadin, 2006: 16).

Here, planning powers are set against not only the poor health and social conditions of the people but also their morals and character. A dichotomy is established between the uplift in conditions to be brought about by town planning as set out in the Act, and popular morality.

The 1909 Act provided local authorities with powers to prepare schemes for ‘controlling the development of new housing areas’ (2006:16). It focused its attention here because these were where most influence could be had: legislation running to catch up with uncontrolled development.

The new planning powers were couched in questions of housing that stretched back through public policy and the actions of earlier philanthropic organisations (1954:181). For many involved in social and environmental reform in this period, public health was a convenient narrative when advocating for greater state planning powers, and one with powerful, emotive connections.

If the emergence of town planning legislation was charged with an paternalistic and oppositional sense of the public and their character, a somewhat different approach was being developed by the architects and planners who were giving architectural and urban form to the town planning movement, through the design and delivery of the first garden cities and suburbs.

The architecture and urbanism of Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin, which was the first to give substantial form and aesthetics to the ‘garden city’ ideals of Howard and the Garden Cities movement, was rooted in the socialist aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts – Unwin hung portraits of William Morris and Edward Carpenter above his drawing board (Hardy, 2000:68) and had been a prolific contributor to Commonweal, the Socialist League newspaper (Cherry, 1981: 74). Accordingly, Parker and Unwin’s work ‘looked backward’ to the medieval city, to the neo-medieval utopian environment of Morris’ Nowhere, to the English vernacular of the 16th and 17th centuries, and to the Germanic town planning tradition established by Camillo Sitte (1981: 74).

Unwin’s Town Planning in Practice, published to coincide with the 1909 Act (1909: ix) and repeatedly reprinted, looked closely at this field of references and codified them for use in applying town planning principles in the wake of the Act. Unwin’s writing makes no judgements on the public in the manner of Burns. Instead, the public is drawn, as Esher (1981: 17-18, 27-28) asserts, in terms couched in nostalgia and escapism. The book was illustrated with nostalgic drawings of peasant-populated picturesque English village streets, by C. P. Wade. Following Morris, Unwin’s work harked back to an idealised feudal era and sought to rescue urban form from that period and to repurpose it for the present. In the closing chapter, Unwin wrote:

In feudal days there existed a definite relationship between the different classes and individuals of society, which expressed itself in the character of the villages and towns in which dwelt those communities of interdependent people. The order may have been primitive in its nature, unduly despotic in character, and detrimental to the development of the full powers and liberties of the individual, but at least it was an order. (Unwin, 1909:375).

For Unwin, the ‘growth of democracy’ (ibid.) that he saw occurring in society had destroyed that old feudal order for the sake of individual freedom, but at the cost of communality and cooperation, and he equated the growth of the town planning movement with a new spirit of cooperation that would address this.

It is coming to be more and more widely realized that a new order and relationship in society are required to take the place of the old, that the mere setting free of the individual is only the commencement of the work of reconstruction, and not the end. The town planning movement and the powers conferred by legislation on municipalities are strong evidence of the growth of the spirit of association. (ibid.)

These words provided an intellectual framework through which the co-operative and communal qualities that Unwin saw in the architecture and settlement patterns of the past could be brought as exemplars – draw, described, built - into the present.

Social history would reveal the naïveté of this. If the domestic architecture of Letchworth, Welwyn and Hampstead Garden Suburb emphasised collective, ‘cooperative’ forms of dwelling and harked back to the communal dwelling types of the monastery and the quad, forms of dwelling in which the individual is subsumed within a larger collective identity – a form which also appears in Unwin’s ideal density diagrams of Nothing Gained by Overcrowding (1912), in which low-density dwellings frame communal areas for sports and food production. But it would be the detached and semi-detached versions of these prototypes that would catch the imagination of the population at large.

In the wake of the 1909 Act, at the macro level the model of town planning advocated by Unwin became the dominant form of suburban development. Ideas which had been rooted in public health reform and a rejection of nineteenth century industrial sprawl had combined with the aesthetic ideology of the socialist-enfused Arts and Crafts to provide both the impetus and the language for a new generation of speculative development that now further swelled the city and colonised the countryside, in ways utterly beyond the control of the nascent statutory planning system (Ashworth, 1954:195).

This influence, in the majority of cases, took Unwin’s pronouncements about low density (1954:195) and aesthetics and little else. There is little of Ebenezer Howard in the typical interwar suburb, whether built by the state or the speculator, but it owes much to the architecture and landscapes of Letchworth and Hampstead Garden Suburb.

The manner by which town-planning had become allied to intervening on the fringes of towns and cities was understandably an outrage to many within the Garden City movement (1954:196), for whom new settlements, not low-density estates on the urban periphery, were the only acceptable model. For this movement, it was clear that more ambitious planning powers would be needed than the limited ones conferred by the 1909 Act. The Act’s focus on improvements at the scale of the ‘scheme’ left it with nothing to say about the consequent expansion of that ‘scheme’ across the countryside.

For advocates of planning in this period, it quickly became obvious that nineteenth-century industrial sprawl had one advantage over the new form of development that the 1909 Act had ushered in: it was compact. The new interwar sprawl led to better conditions for its residents but at the cost of large areas of the countryside. The advocates of statutory planning now found themselves in opposition to the very places that the first wave of statutory planning had played a role in creating (Hall & Tewdwr-Jones, 2011: 23-25) and the resulting discourse took on a markedly class-based narrative that would come to dominate calls for a national planning system in the UK.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, the concentration of the British working class in industrialised cities and towns was being replaced with a ‘new landscape of dispersal’ (Hardy and Ward, 1984: 1) which the 1909 Act had played a role in bringing into being. The transformation was profound.

England was suddenly a smaller place. Beyond the suburbs, themselves a product of people moving out, the new ways were soon to make their mark. Roadhouses along the arterials, teahouses perched on clifftops, riverside hotels, petrol pumps in picturesque villages, advertisements painted on cottage roofs and walls, charabancs and caravans all bore witness to a process of dispersal. (Hardy and Ward, 1984: 1)

For Esher, the post-WWI period can be understood as one of ‘prelapsarian innocence’ (Esher, 1981: 16-17), prior to the devastations of World War II and the atomic bomb. His and Hardy & Ward’s descriptions evoke the physical impacts on the British landscape of a whole range of new freedoms that had emerged in the early years of the twentieth century which had most meaning for working class and emerging middle class populations. As well as transforming social relations – (the number of people working as servants reduced by 1 million people between 1911 and 1921, Todd, 2014: 30) - these freedoms, combined with agricultural depression and other economic factors, rewrote the logic of the English landscape in unprecedented ways.

The early twentieth century, particularly the 1920s and 1930s, saw radical changes in the ownership and use of land beyond the traditional urban centres. It saw the outward sprawl of towns and cities, consuming acres of open land in a compelling quest for more spacious housing; it saw the fragmentation of agricultural estates and the sale of smaller farms which had been used as farmland for centuries; and, finally, it saw an unprecedented search for quiet beauty spots, country lanes, hilltops with views, woodlands and rivers and, most of all, for a stake along a diminishing natural coastline. (Hardy & Ward, 1984: 16)

Or, most baldly:

In the four years after the First World War, one- quarter of the area of England was bought and sold, a rate of land disposal that had not been witnessed since the dissolution of the monasteries. (O’Dell, 2000: citing Newby, 1979).

Prior to World War One, as we have seen, planning advocates such as Unwin could invoke the archetypal English feudal village without recourse to sociological analysis or tackling the spatial and political implications of a de-densified and regulated village form on the character and organisation of the British Isles if applied at scale. In this context, drawings such as those found in Nothing Gained by Overcrowding (1912) could look with great intelligence at ‘housing’ at the scale of the street, without exploring at the macro-scale impacts of the proposals they represented.

By the interwar years however, the working class and lower middle class reoccupation of the countryside had become a tangible reality, a spatial analogue to the deep changes occurring in society, and it was increasingly difficult to discuss town planning in any other way than through class. Improvements for those at the bottom of the class structure had become a threat to the ‘amenity’ and lifestyles of those nearer the top. Long-held aesthetic ideals concerning the ideal form and appearance of the countryside, generated and held by a social elite, were fundamentally challenged by an apparently uncontrollable lower-order colonisation of that countryside, and existing legislation could do little to address the process.

The architect Clough Williams-Ellis was a devoted campaigner for coordinated national scale planning powers. He achieved a significant audience for the issue through his published works and broadcasts, and his calls for a national statutory system, made in the wake of the failings of the 1909 Act and the explosion of interwar suburbs, took on a hegemonic character.

In England and the Octopus (1928), the titular octopus is understood as uncontrolled development, sprawling outward from towns as ‘ribbon development’ (following arterial roads). Williams-Ellis’s arguments have implicit class implications:

For – need it be said? – it is chiefly the spate of mean building all over the country that is shrivelling up the old England – mean and perky little houses that surely none but mean and perky little souls should inhabit with satisfaction. (Williams-Ellis, 1928: 15)

The inhabitants of these ‘mean and perky little houses’ are emphatically not the same as the inhabitants of the fine villas that Williams-Ellis holds up as exemplars, or indeed produced tributes to in his design work.

Williams-Ellis draws up a list of questions that every new building should try and respond to, with the sixth and final question being:

Are you a good neighbour – do you love the Georgian inn next door, or the Regency chemist’s shop opposite, or the pollarded lime trees, or the adjoining church and elm grove, as yourself? Do you do-as-you-would-be-done-by? Do the other buildings and the hills and trees and your surroundings generally gain or lose by your presence? In short, have you civilised manners? (1928: 95)

The elements of the street scene that Williams-Ellis identifies as having ‘civilised manners’ reflect a particular set of value systems and indeed the fashions of the day among the tasteful and powerful: Williams would later become an early member of The Georgian Group (founded 1937), a preservationist organisation but also one that encompassed modernist values (through members such as John Summerson and Nikolaus Pevsner) and which valued the perceived aesthetic and moral certainties of the Georgian period. Lytton Strachey’s writings of the time evoke the Georgian period as one of ‘delight and repose… framed and glazed, distinct, simple, complete’:

‘this was a fantasy, of course, but what fascinated [him] was that, through a time of almost continuous war and political turmoil, polite society had managed to invent for itself an image of orderliness and leisure. It glazed the picture and smoothed the creases.’ (Harris, 2010: 60)

In contrast to the disorder of popular building activity, the radical aesthetics of European modern architecture (for instance the writings of Le Corbusier, translated by Frederick Etchells, a founder member of the Georgian Group) were readily absorbed within Williams-Ellis’s framework of good manners. Modernist and Georgian architecture both represented order and taste, and in this context neither were seen as threatening to any existing power structures. The socially-derived modernity of the semi-D and the plotland sunburst were far more of a threat than any intellectually-derived Modernism.

Williams-Ellis et al. were aesthetically in tune with Whitehall, and its endorsement (partly through the influence of Raymond Unwin) since 1919 of a ‘neo-Georgian’ approach to its state-funded cottage estates, such as at Becontree (Jackson: 1973).

Williams-Ellis understood the spatial problem at the heart of the recent development of Britain, and the scale of the threat, and advocated for a greater distinction between town and country, abhorring the blurring of these conditions represented by much suburban and plotland development, without acknowledging the contribution of early state planning initiatives to this condition (1928: 21).

Williams-Ellis’ approach can be understood as the town planning equivalent of ‘knowing your place’, deriding the inner city slum or tenement but finding it preferable to the ‘lower orders’ colonising (or, in fact, re-colonising) the rural. In counterposition, he proposed that ‘citizenship’ be taught in schools in order to improve the public’s sense of, and ambition for, the built environment, but ultimately he knew that it would take national-scale organisation to systematically address the evils that he and many others saw in what was happening to the UK:

Let us so arrange things, so revise our laws and by-laws and public opinion, that the homes of the people are no longer disfiguring eruptions on the face of the land, but a welcome and becoming adornment, as they were in the days when England was beautiful because of them. (1928: 40-41)

Private ownerships, vested interests and finance would all be difficult to deal with – obviously – but it could be done. It would mean parliamentary powers, large loans and heroic measures generally; but it could be done. (1928: 45)

Williams-Ellis also realises that such an intervention would have to be a response to popular demand (‘the more intelligent of the general public have definitely begun to care about amenity’) (1928: 120), and therefore crucially recognises the role of the propagandist (or public intellectual) in building this desire among the populace: ‘…demand must be made by the public at the instigation of the propagandist.’ (1928: 115-116) Propaganda, and the building of ideological movements outside of government in order to effect social or political change, was very much in the air, and whilst writing England and the Octopus (and its collaborative sequel Britain and the Beast) Williams-Ellis must have been strongly aware that he was part of a growing group that was moving – in terms of both action and rhetoric – toward becoming a strong, coherent campaigning voice for preserving a vision of England rooted in the landscapes and class certainties of the past century.

Though he would become one of the most influential ‘public’ planners of the postwar age, Patrick Abercrombie at this time was significant for his bridging between the preservationist movement and the growing professional population of progressive planners. In 1926, he published ‘The Preservation of Rural England’, a text which called for the formation of a national committee to preserve the English countryside. Before the year was out, the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE) had been formed, with Abercrombie as its Honorary Secretary. The CPRE quickly became a powerful lobbying organisation, providing the government of its day with advice on how to use its own legislative powers to prevent (or dissuade) ribbon development (Hunt, 2006:3), was soon advocating for national parks, and campaigned successfully in favour of several key pieces of pre-1947 planning legislation which variously expanded or consolidated the 1909 Act.

Abercrombie and Williams-Ellis were certainly not anti-development, but both believed in a power structure where a state system of statutory planning would ensure that development would happen ‘properly’:

the preservationists who established CPRE were remarkably open to the idea of change in the countryside, provided it was properly planned and, it must be said, provided that people like them helped guide it. (Spiers, 2009: 2)

As Wild (2004) and Newby (1987) both assert, the ‘people like them’ should not simply be written off as a homogeneous cultural elite fearing and denigrating the lower orders, but as a more complex conjoining of unlikely bedfellows, albeit all viewing the situation from a position of privilege:

The membership was drawn from a wide range of professions and callings, but consisted almost exclusively of a middle- and upper-class cultural elite. It included academics, town and country planners, writers, broadcasters, landowners and even a few Fabian socialists; people who, despite their different occupational backgrounds and political convictions, had a shared belief that the protection of the rural landscape, supported by strong government regulation, was of paramount importance. (Wild, 2004: 145)

“The preservation movement proved to be a strange amalgam of patrician landowners, for whom the preservation of the countryside was closely linked to their conception of ‘stewardship’, and socially-concerned Fabians (Hampstead dwellers, but keen hikers on the Downs) who believed in the pursuit of social justice through national planning.” (Newby, 1987, quoted in Spiers, 2009: 2)

The movement therefore contained both progressive, pro-development impulses and more conservative, literally preservationist tendencies, all, for a period at least, containable under the uniting notion of propriety. This propriety, all agreed, would be best maintained ‘under the guidance of an expert public authority’ (David Matless, cited in Spiers, 2009: 2).

As Wild observes, the movement to preserve, both formally within the CPRE and in the culture more generally, was by this time no longer composed only of ‘great men’ with professional expertise in the subject of planning and development, but had also begun to attract the support of individuals from outside of the discipline, among them influential authors J. B. Priestley and E. M. Forster. The planning historian John Punter has highlighted the class dynamics of this movement:

‘What was really at stake in reproaches like these was the threat that widening suburbia and mass enjoyment of the countryside presented to the ‘culturally selfish’ – those privileged and well-off people who, in terms of where they lived and where they spent their leisure, were already ‘in possession’ of rural Britain. Viewed in this light, the ‘defence’ of the English countryside may be seen as a class resistance. (Wild, 2004: 137)

Viewed in this light, notions such as propriety and preservation can certainly be understood as form of cultural hegemony. The ‘old England’ of Williams-Ellis is the old England of pre-WWI class certainty, and of a working class population firmly wedded to long-established protocols, relationships to higher classes, and to industrial urbanity. It is a feudal England where industrial Manchester, or the Pool of London, are unseen, where urbanization stops at the market town, with the village held up as the ideal form.

Plotland complexes were ephemeral, unsightly, anarchistic, and an affront to good taste: in complete contrast, the long-established English village, despite several decades of depopulation and an increasing momentum of social and cultural change, was still seen as ancient, cohesive and aesthetically correct. (Wild, 2004: 141)

Those who held up the village whilst doing down the suburb were aware that the archetypal English village was as much a product of ad-hoc, piecemeal development, what we would now term ‘emergent’ environmental procedures, as the suburb of the day, but they were the result of rigorous, containing power structures of the recent past that early town planning legislation had failed to replace. In his wartime work Town Planning, Abercrombie would explicitly relate the ‘ribbon development’ of his day (and which the CPRE had set itself up in opposition to) to the pattern of growth common to villages, that of growing dwellings and other buildings along the lines of existing roadways and routes: ‘Ribbon building is of course the natural formation of all communities’ (Abercrombie, 1943: 119-120). There is a tension, then, in the preservationist movement’s alliance with the planning movement; a harking back to an ideal rural environment that had not received a ‘plan’ in a manner that any planning advocate of the time would recognise. Abercrombie recognises this tension in his writing, noting that:

[The exercise of planning] has not been a matter of civilization… there have been whole periods and whole countries, both regarding themselves as civilized, when natural growth – really synonymous with complete muddle - has happened… Planning is… not a question of unconcerned growth, even though the latter may produce fortuitously happy results (1943: 10-12)

Here, we find Abercrombie attempting to find ways of appreciating the unplanned environments of the past whilst firmly advocating for the planning of the present and future. The implication is that the happy accidents of an unplanned system are not worth the risk of muddle.

Writing in the face of rising Fascism across Europe, George Orwell made a passionate attack on the class assumptions and prejudices of the English socialist movement in his 1937 text The Road to Wigan Pier. Orwell himself was far from a defender of suburban development, as can be implied from his novel Coming Up For Air. However, concerned about what he saw as the problems of English socialism as he read it in the 1930s, The Road to Wigan Pier ends with a well-aimed attack on a privileged, patrician socialist movement, seeking not emancipation or equality but a form of order.

The underlying motive of many Socialists, I believe, is simply a hypertrophied sense of order. The present state of affairs offends them not because it causes misery, still less because it makes freedom impossible, but because it is untidy (Orwell, 1937: 156-7).

Orwell saw clearly the prejudices - taste, manners, class – that are implicit in the writings of Williams-Ellis and others, and he understood them as a fundamental barrier to the transcending of class structures in the name of social change. The need for ‘tidiness’ that Orwell identifies is a close relation of Williams-Ellis’ ‘civilised manners’ and propriety. It betrays the interest of left-leaning but essentially patrician figures such as Williams-Ellis in the idea of socialism (CW-E was a paid up member of the Independent Labour Party) but in ways that would not disturb the power structures of old England. Restoration, not revolution.

Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the Great War, housing and public health reform briefly took on a literally counter-revolutionary urgency in the minds of politicians and civil servants. As Swenarton (1981) explores, the urgency of post-WWI public housebuilding was closely informed by fears of a working class uprising on a national scale, something that was widely feared among the political classes in the wake of the Russian Revolution.

It was believed that, as the Parliamentary Secretary to the [Local Government Board] put it in April 1919, ‘the money we are going to spend on housing is an insurance against Bolshevism and Revolution.’ (Swenarton, 1981: 79)

The state’s role in this period contributed to a spatial revolution that was in its way just as significant as the social revolution that it feared. In the vast commercial civic environment of the State Cinema in Barkingside, in the queues outside pubs at Becontree, in the sunburst on a garden gate, in the agency grasped with both hands by the ‘little man’ building his own home in an Essex field, we can see a reclamation of the English landscape in ways that struck to the core of power relations within English society, and which left planning advocates explicitly seeking national-scale planning powers to recalibrate the nation’s land use back toward the ‘proper’. In this context, Thomas Sharp could convincingly and in a mass market paperback (the only ever best-selling book about planning ever published) argue that

It is no overstatement to say that the simple choice between planning and non-planning, between order and disorder, is a test-choice for English democracy. (Sharp, 1940:143)

The national planning system advocated by Williams-Ellis, Forster, Priestley, Abercrombie, Sharp et. al came into being in 1948, as enshrined in the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, and (unsurprisingly) it was immediately used against the plotland developments that were the ‘enemy’ of two decades of preservationist rhetoric. An early instance of this was at ‘Bungalow Town’ in Sussex (Hardy & Ward, 2002:91-102), a place we have already explored at the beginning of this piece, which was destroyed when the newly-established planning authority, in one of the UK’s first experiments with new powers enshrined in the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, compulsory purchased and demolished the entire settlement barring the church and a few one-off houses.

During the public enquiry, language appeared that could have been lifted directly from the interwar rhetoric of Williams-Ellis, with calls to ‘clean up this appalling mess’ (2002:97). The hegemonic character of pre-war planning discourse had begun to directly infiltrate state activity and would go on to have a much wider and more pernicious influence on the nature of centralised planning, an influence that we are yet to escape.

Esgairgeiliog Ceinws, 2017.

Bibliography

Abercrombie, Patrick (1924) The Preservation of Rural England. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Abercrombie, Patrick (1943) Town and Country Planning (Second Edition). Oxford: OUP.

Ashworth, William (1954) The Genesis of Modern British Town Planning: A Study in Economic and Social History of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Bennett, Tony, Colin Mercer and Janet Woollacott (1986) Popular Culture and Social Relations. Milton Keynes: OUP.

Bowie, Duncan (2017) The Radical and Socialist Tradition in British Planning: From Puritan colonies to garden cities. London: Routledge.

Briggs, Asa (1968) Victorian Cities, revised edition. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Cherry, Gordon E. (ed.) (1981) Pioneers in British Planning. London: Architectural Press.

Cullingworth, J. B., and Vincent Nadin (2006) Town and Country Planning in the UK (Fourteenth Edition). London: Routledge.

Esher, Lionel (1981) A Broken Wave: The rebuilding of England 1940-1980. London: Allen Lane.

Gramsci, Antonio, (eds. Quentin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith) (1971) Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Hall and Tewdwr-Jones (2011) Urban and Regional Planning: Fifth Edition. Oxon: Routledge.

Hardy, Dennis (2000) Utopian England: Community Experiments 1900-1945. London: E & FN Spon.

Harris, Alexandra (2010) Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper. London: Thames & Hudson.

Howard, Ebenezer (1898) To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. London: Swann Sonnenschein (republished in facsimile edition (2003) with a commentary by Hall, P., Dennis Hardy & Colin Ward)

Hunt, Tristan (2006) Making Our Mark: 80 years of campaigning for the countryside. London: Campaign to Protect Rural England

Jackson, Alan A. (1973) Semi-detached London: Suburban Development, Life and Transport, 1900-39. London: Allen & Unwin.

Joll, James (1977) Fontana Modern Masters: Gramsci. London: Fontana.

Laclau, Ernesto and Chantal Mouffe (1985. Second Edition 2001) Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

Morris, W. (2003). News From Nowhere. Leopold, D (Ed.). New York, Oxford University Press Inc., New York.

Mouffe, Chantal (ed.) (1979) Gramsci and Marxist Theory. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Newby, Howard (1979) Green and Pleasant Land? Social Change in Rural England. London: Hutchinson. (Edition consulted: 1980, Harmondsworth: Penguin)

Newby, Howard (1987) Country Life: A Social History of Rural England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

O’dell, Sean “Holiday plotlands and caravans in the Tendering district of Essex, 1918-2010”, The Local Historian Volume 42, No. 2, May 2012.

Orwell, George (1939) Coming Up For Air. London: Victor Gollancz

Orwell, George (1937) The Road to Wigan Pier. London: Victor Gollancz (Edition consulted (1967, Harmondsworth: Penguin)

Priestley, J. B. (1934) English Journey. London: Heinemann

Sharp, Thomas (1940) Town Planning. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Spiers, Shaun (2009) 2026 A Vision for the Countryside. London: Campaign to Protect Rural England.

Swenarton, Mark (1981) Homes Fit for Heroes: The Politics and Architecture of Early State Housing in Britain. London: Heinemann.

Todd, Selina (2014) The People: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class 1910-2010. London: John Murray.

Unwin, Raymond (1909) Town Planning in Practice: An Introduction to the Art of Designing Cities and Suburbs. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

Unwin, Raymond (1912) Nothing Gained by Overcrowding. London: King & Son.

Ward, Colin (2002) Cotters and Squatters: Housing’s Hidden History. Nottingham: Five Leaves.

Wild, Trevor (2004) Village England: A Social History of the Countryside. London: Tauris.

Williams-Ellis, Clough (1928) England and the Octopus. London: Geoffrey Bles.

Williams-Ellis, Clough (ed.) (1937) Britain and the Beast. Letchworth: J. M. Dent & Sons.

Williams-Ellis, Clough (1971) Architect Errant: The Autobiography of Clough Williams-Ellis. London: Constable.

Wolters, N.E.B. (1985)Bungalow Town: Theatre & Film Colony. Shoreham: Marlipins Museum.