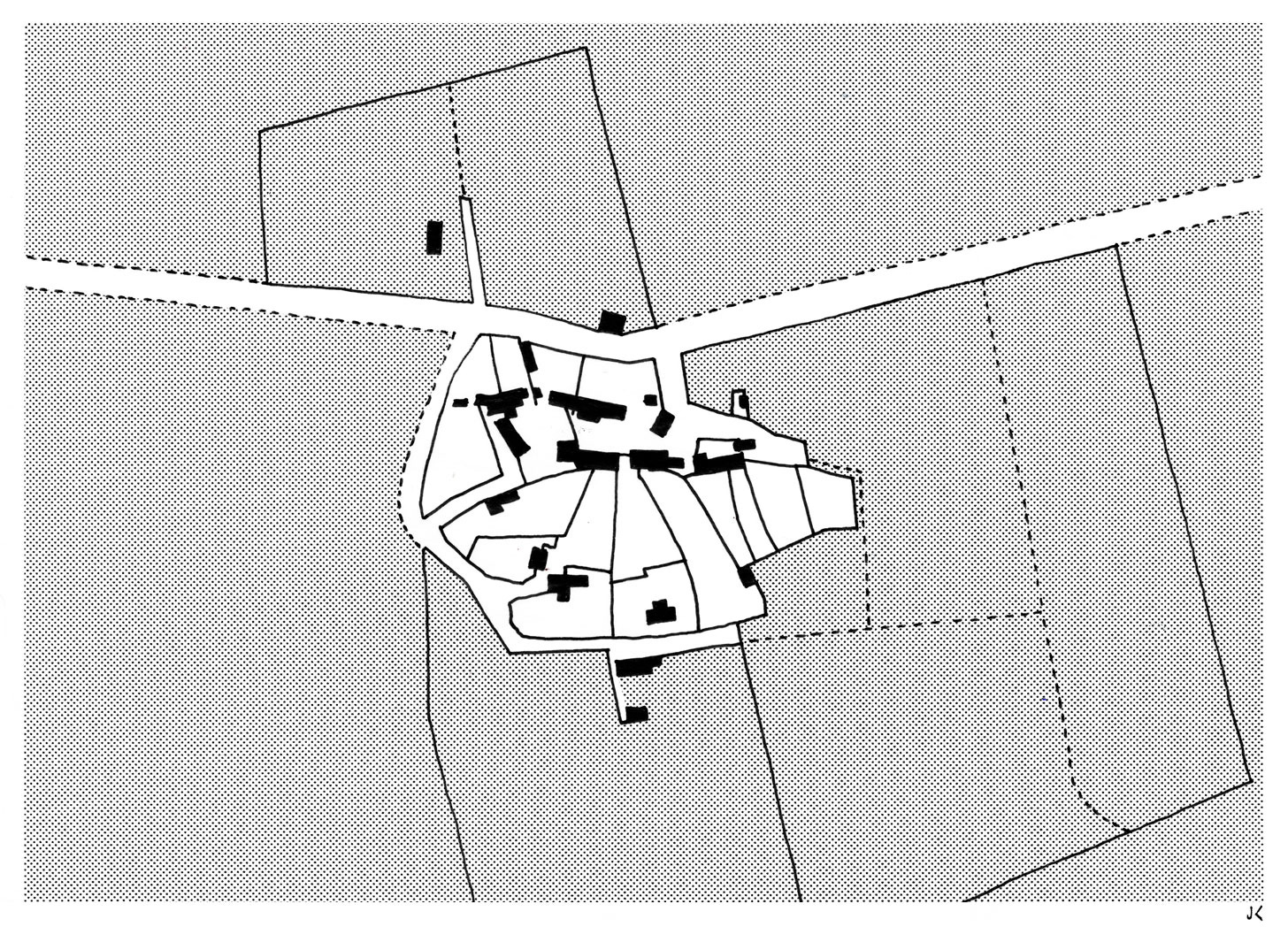

Other Plans #2: Clustered Hamlet (Juniper Hill)

A ‘squatted’ hamlet encircling a public house.

Other Plans is an occasional series of essays, each of which explores a particular alternative method of ‘doing’ spatial planning drawn from history. Each essay ends with a speculation on the use of this ‘other plan’ in the present or near future.

Tucked slightly away from the road, the settlement is a cluster of one- and two-storey stone and brick dwellings organised informally like rose petals around a central, large dwelling, which after a time transformed into a pub, the hamlet’s only non-domestic building. Instead of being organised along lanes or streets, the homes appear to have grown on the back of each other’s plots, somewhat like cell division, and the whole settlement of homes is encircled by an unmetalled road that wraps around and thereby contains it. Nowadays, each dwelling has its own vehicular entrance from this road but once upon a time the routes between dwellings, between dwellings and the pub, and between every building and the wider fields and allotments, were once simply about walking from plot to plot, with no connecting tissue or public space between them in the form of lanes or footpaths. The hamlet is simply individual dwellings and plots, sometimes sharing a party wall, clustered together against adversity.

Juniper Hill is a small isolated hamlet on high Oxfordshire land in the parish of Cottisford, on the very edge of the county’s boundary with Northamptonshire, and when originally settled it nestled in a swathe of Juniper bushes, very few of which now survive. As a settlement it originates in a pair of houses built for the poor of the parish by the local Overseers of the Poor in 1754, on Cottisford Heath, then common land in the possession of the Tusmore Estate and Eton College. This common land was a vital asset to the local farming communities as it provided space for commoners’ rights to be exercised -grazing and foraging for example. Later, another two poor houses were added, and by the mid nineteenth century, there were four freeholders at Juniper Hill and potentially around 25 other dwellings, all built as ‘squats’ or encroachments on the land in a way that was most-likely tolerated by local tenant farmers because their inhabitants’ labour was vital to the local economy. In 1848 the ultimate land owners of Cottisford Heath procured an order to enclose the lands and remove them from the commoners’ use, and were met with violent resistance over a period of several years, until things came to a head and a team of 20 men were dispatched to threaten the demolition of the settlement itself, an act of repression which ultimately led to a compromise between landowner and villager. The squatters were ‘given’ the right to harvest that year’s crop and also 14-year leases on their dwellings with a nominal rent payable, with ownership stated as reverting to the landowner at the end of that period, and additionally both allotment grounds and a recreation ground were provided to villagers. There is no evidence that these leases were ever brought back into the landowners’ hands, and the cumulative evidence suggests that the landowners in this instance, whilst determined to exercise the principle of enclosure, also to some extent depended upon or otherwise wanted to retain the labour value of the Juniper Hill residents.

It appears that the central house (could it have been one of the original poor houses around which the hamlet grew?) had become a pub a while before the 1880s, allowing each resident of the hamlet to walk across their own plot (and potentially those belonging to a couple of their neighbours) in order to reach the pub’s doors of an evening. The pub’s name, the Fox, is almost certainly in tribute to George Fox, one of the original squatters who had built his own home at Juniper Hill in the 1840s.

The reason why we know so much about Juniper Hill is thanks to the writer Flora Thompson, whose work Lark Rise to Candleford (in fact a trilogy of novels published in a collected edition in 1945) fictionalised Juniper Hill as Lark Rise (a name actually taken from one of the local fields). Thompson’s work was published at a particular moment, when fears about technological progress, social transformations and indeed global war all led to a fascination with rural traditions that were seen as passing into history. Though Thompson herself always presented her work as fiction (albeit lightly fictionalised, with the protagonist named Laura and clearly based upon herself), her deftly-written work captured the national mood and frequently – even to this day in some quarters – has been presented as documentary or memoir. Barbara English’s 1985 essay in Victorian Studies unpacks the difference between factual Juniper Hill and fictional Lark Rise, exposing the more turbulent battle between squatters and landowners that Thompson had somewhat smoothed over. For decades, those seeking a picture of nineteenth century rural life found a consoling and deeply humane narrative in Thompson’s writing, indeed they still do, but they would not find the more traumatic and violent narratives that actually underpinned the existence of the settlement of her birth.

The Fox public house closed in the late twentieth century, becoming a private home, but the other houses, the fields of allotments and the recreation ground remain. The ‘rose petal’ housing plots also remain as a compelling piece of rural urbanism, a beguilingly informal ring of homes clustered around the pub – not too close, not too far. Aside from providing a history of English land enclosure in human-scale microcosm, Juniper Hill also stands as a compelling example of a settlement arising out of necessity (that of agricultural labour) and being largely tolerated and accepted on this basis – this uneasy tolerance was a normal state of affairs both before and after the crisis of enclosure, as suggested by the fact that the leases were seemingly never reclaimed. The result was a peculiar, informal and emergent form of settlement, eloquent about the kinds of community structures and forms of association that people are able to form when left to their own devices.

maps.app.goo.gl/D2KMTnBtVE2CeR9b7

Bethnal Green, 18 July 2025.

Acknowledgements

Aside from Flora Thompson’s writing I am indebted to Richard Mabey’s biography of Thompson, Dreams of the Good Life, and the essay "Lark Rise" and Juniper Hill: A Victorian Community in Literature and in History by Barbara English, an essay in Victorian Studies , Autumn, 1985, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 7-34, published by Indiana University Press.