It is said that if you dig the soil in London or St Albans you will know when you have reached the 1st century AD because the soil is suddenly charred and blackened - this is the layer of the city that was burnt to the ground by Boudicca. Similarly, going through the history of many of Britain’s coastal or rural settlements, you will know you have reached the years around World War 1 by the sudden presence, in historic postcards, photographs or maps, of a sudden rash of popular, handmade timber constructions - typically on previously underdeveloped land: farmland, woodland or coastal.

The working classes of the British Isles had been divorced from the rural environment by the pull of the industrial revolution - which centralised work and access to capital in urban areas - and by the push of land enclosure, the combination of which severed historic relationships of the rural poor with the land and established a new hierarchy of town and country. When I trace my own family history I find a multitude of rural labouring poor scattered loosely across the Sussex and Suffolk countryside, before a massive exodus into the growing urbanity of Brighton in the early to mid nineteenth century. The impacts of this shift were complex and multiple, but in this context the key shift was into industrialised dwellings - the ‘back to backs’ and repetitive brick terraces that would swiftly, by the turn of the twentieth century, become demonised by early town planners and progressive architects.

While those planners and architects were conceiving of solutions to this industrialisation of dwelling and settlement (chief among them the Garden City), the working classes themselves were finding their own solutions, particularly in the wake of World War I and an array of other transformations, among them the popular expansion of rail travel and rapidly falling agricultural land values. The resulting settlements were what we now call ‘plotlands’ - land that was unfavourable except for its rural location, divided up into small plots and sold, chiefly to working people and mostly under the banner of holiday or weekend leisure plots. What actually happened, of course, was that whole towns emerged, and in an era before organised state planning they emerged in significant numbers. They’re there in advertisements within the pages of the popular press of the time, they’re the shacks that serve as a pivotal setting in Winifred Holtby’s South Riding and in agit-prop pageant plays by E.M. Forster, they’re the rhetorical ‘octopus’ of uncontrolled development that informed the birth of rural preservation movements and indeed of the very idea of state planning.

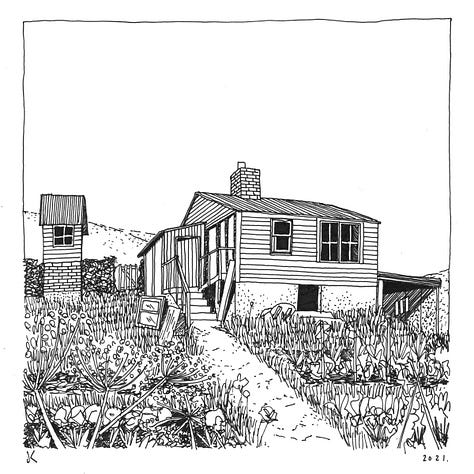

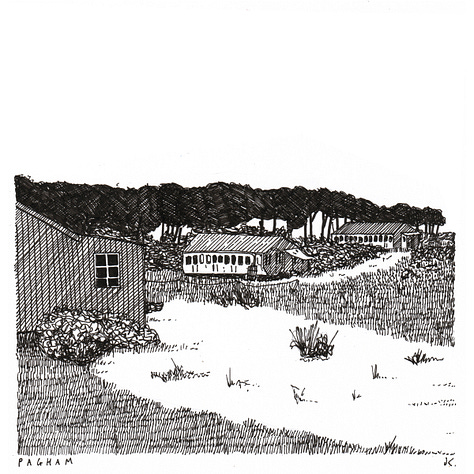

Architecturally, these buildings were works of improvisation, DIY craft and opportunism, often relying on existing, ‘as found’ structures such as tramcars or railway carriages (there is a record of redundant bathing machines being used as dwellings in Woodingdean, just outside Brighton), and otherwise made using materials that could be carried on trains out from the East End of London or under the arm whilst pedalling a bicycle. Their architecture, though often formally inventive and aesthetically complex, was ultimately humble, thrifty and often vulnerable to tide and weather. At its worst it could be overwhelmingly twee or sentimental (the ‘English sunrise’, ‘Dunroamin’), but that’s what you get when popular taste is allowed to explode. But seen as a whole - as a layer in the land like Boudicca, they represent much more than these aesthetics and formal concerns - they stand for a much greater explosion of working people out of the urban realm and back into the countryside, a popular reclamation of the rural that was swiftly and lastingly suppressed. Built in the humblest possible way, and united conceptually and materially with shacks, shanties and popular settlements across the world, these simple buildings represent a massive act of reclamation and restitution which, through their own agency and through resistance to it, changed the landscape of England utterly, ushering in the suburban world that we still to a large extent exist in.

In England, thanks to post-1947 planning legislation, this handmade architecture typically had two fates: demolition or surreptitious survival. In places like Shoreham by Sea, a vast settlement of bungalows made from former railway carriages was substantially destroyed using early compulsory purchase powers (written about at length here), leaving only scattered survivors including the pebble-dashed church. At Dunton, part of Basildon New Town, every plotland home was demolished incrementally except one, which now stands as an unlikely plotland museum in the centre of a nature reserve thanks to the enlightened efforts of conservation volunteers. In places where such destruction was not fully seen-through, examples tended to survive through blending in to the wider ‘normal’ settlement, by ‘becoming normal’ themselves and slowly obscuring or replacing their original tectonic and aesthetic qualities with more mundane or typical forms of cladding, window or roofing panel. And in the context of ever-worsening inequalities and increasingly insane land and property values across much of England, survivors of the period that continued happily on as dwellings are increasingly likely to be swept away in favour of more substantial and higher density dwellings. At Shoreham, when I was a child it was an (admittedly niche) game to try and identify houses that had railway carriages somewhere embedded within them, given away by tell-tale rhythms of windows or occasionally even by original golden lettering: ‘LB&SCR’, ‘third class’. These have now all been swept away; and sadly the loudest preservationist protest has come from the railway history groups and is concerned with preserving not the social history of the settlement or dwelling but rather the original railway carriages. Brilliantly, one such carriage, fully restored to its original 19th century form, is now doing good service on the Bluebell Railway heritage line. As a one-off this is a glorious twist of material fate but it also shares with the demolition imperative the idea that these homes were somehow an aberration or mistake, something best undone or overwritten.

In Essex, as elsewhere, there was so much rural plotland development that controlling it proved to be such a massive headache that large areas remain today. We can see the plotland origins of places like North Benfleet in their unmade roads and loose, gridded urban form, but most of the houses and other buildings have slowly crept toward ‘becoming normal’ - often brick and render masks much older timber frames underneath. And the social potential of the plotland, enabling people to run smallholdings or businesses on their plots as part of the grain of their community, remains real and valued. The sweat equity invested in making these houses in the first place, from scratch and by hand, has paid off, even if at the expense of some of their original character. But so be it.

In places like Sweden and Russia, the idea of a rural retreat, remains real and widely accessible, such that there are vast areas of this sort of development spanning class boundaries and spatial and architectural quality. In England, by contrast, this idea was deliberately stamped out in the postwar period by a process that was highly elitist and classist - ‘the plotholders both get the view and spoil it’ was a contemporary complaint by an established landowner. If, as a child, I would go railway carriage spotting on Shoreham Beach, then today I roam suburban roads on bank holidays and via Google Streetview on the same mission, and the fruits are sweet but few. Here a bungalow built like a colossal verandah shading a long, grand railway carriage. Here a thatched carriage serving as an agricultural store. Here a tramcar repurposed as a home, still serving as such all these years later. Here a bungalow built by the Clarion Cycling Club (motto: ‘fellowship through cycling’) to serve as a clubhouse to further expand access to the countryside to anyone able to cobble together a bicycle. Surviving structures remain united by what they originally stood for - a reclamation of landscape by those who had previously been denied it, taking construction (at the scale of both dwelling and community) into their own hands and exploiting the wider, seismic social transformations of the day, effectively rebooting the urban/rural divide in favour of the masses.

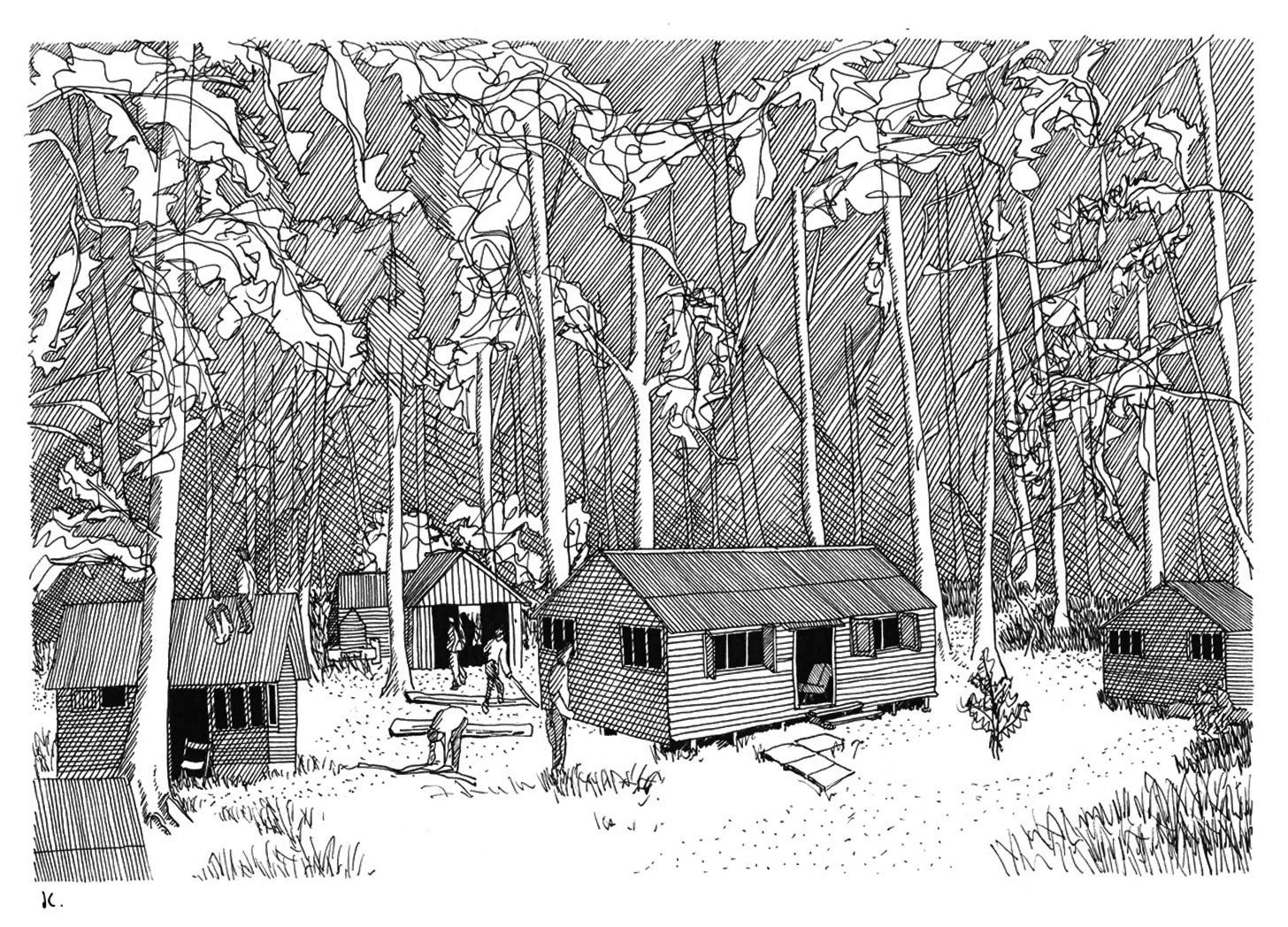

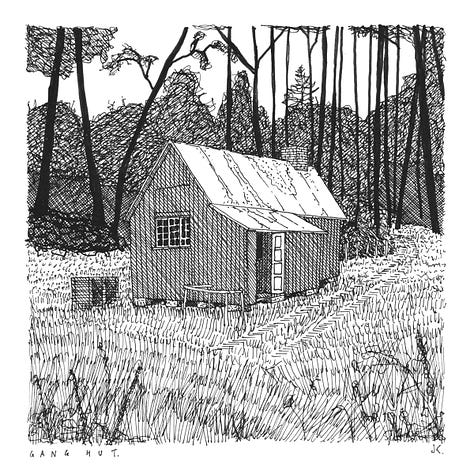

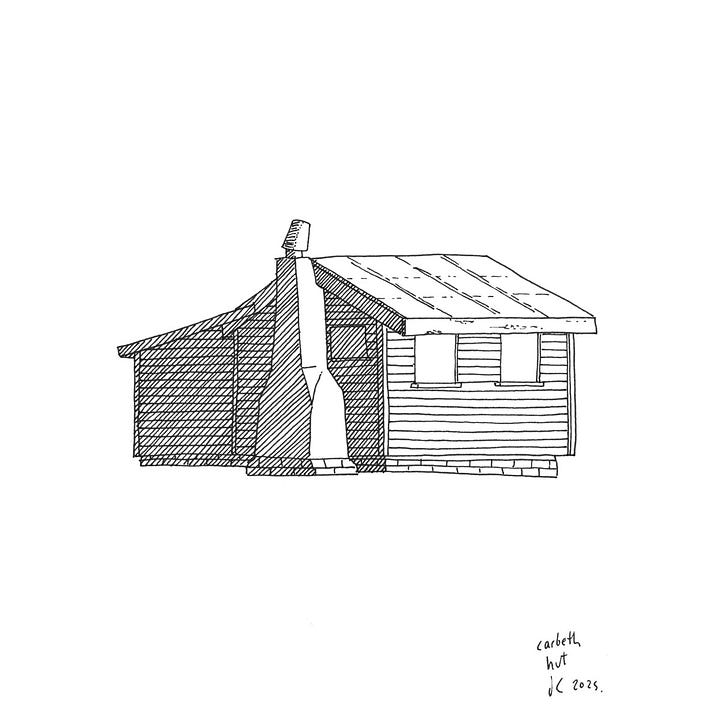

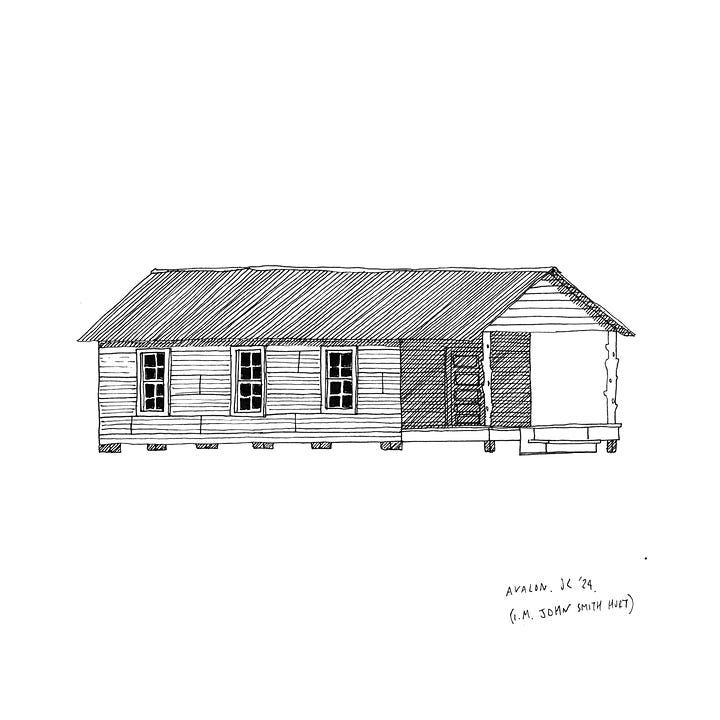

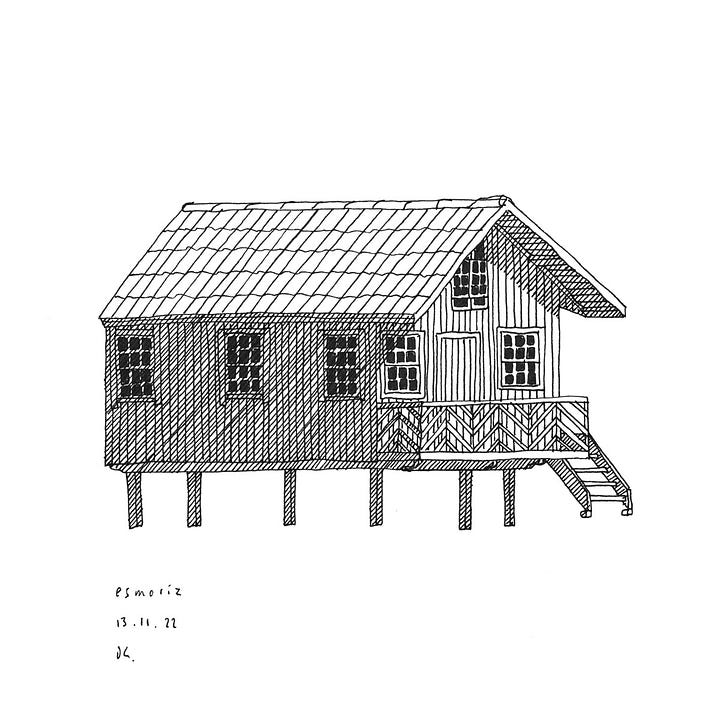

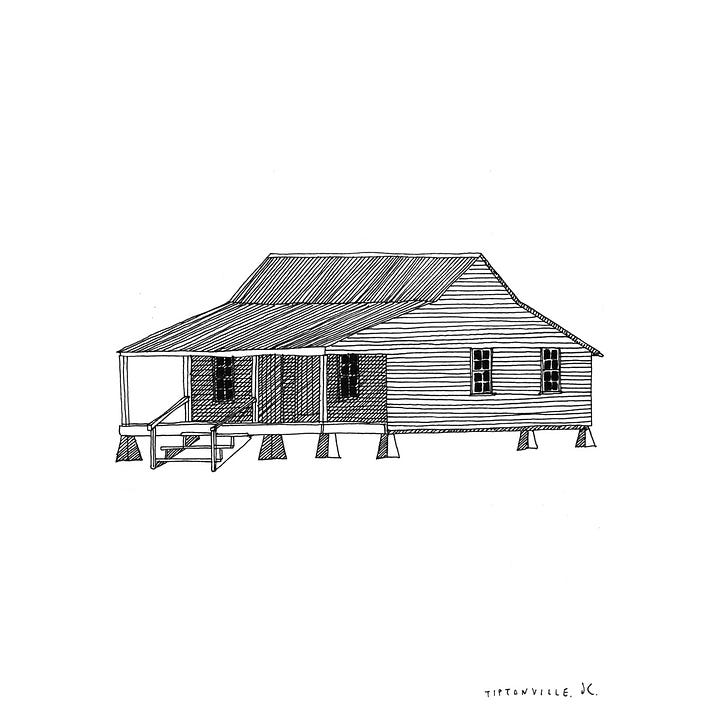

At Dunton and Laindon in Essex, the simple rule - in the absence of public sector involvement - was that every plotholder would lay a single row of paving slabs at the front of their plot in order to build a filigree network of dry pathways across the fields. Residents would use wheelbarrows and prams customised to run on a single wheel to convey goods from the ‘proper’ road to their plots. These forms of collectivised popular construction - where the simple timber dwelling becomes multiple - bring the plotland story into dialogue with other global forms of alternative development - they are cousins of the colonial settlements that took place in New Zealand, for example (the ‘fencibles’), or in Brasil. They are of a piece with the ad-hoc structures not only of the Russian dacha but also of the English allotment shed and the pigeon loft, serving a similar role as refuge and respite. They are closely related to the types of dwelling and settlement structure that Mississippi John Hurt, Dolly Parton, Carl Perkins and Elvis Presley all emerged from in the United States- leading to the one-off preservation of these special examples when all other examples have been long-since cleared away. They are of a family with intentional radical communities of the same era, such as the anarchist colony of Whiteway in Gloucestershire (where every dwelling except the already-standing farmhouse was originally of light timber construction). Or the Sanctuary in West Sussex where Vera Pragnell divvied-up woodland in her ownership amongst a wildly varied community of drop-outs, creatives and those pursuing alternative lifestyles, among them the writer Laurie Lee. Or the greenwood bunkhouses of Grith Fyrd and Forest School Camps, where young men damaged by war were trained to build dwellings and exist in harmony with nature, healing their lungs as they went (the results of whose labours were still standing when I was a child and are now long gone). Or the very similar structures developed by the Woodcraft Folk in places like Cudham or West Hoathly in order to give urban children the gift of the countryside. Or the decorative timber vardo caravans of the Roma tradition, intricately crafted and yet lightweight enough to be pulled day-in, day-out by solo horses. Or the post-WW1 hutting movement that led to whole neighbourhoods of woodland dwellings for ex-servicemen in the Scottish countryside. Or to the long, ancient tradition of timber-framed dwellings in Sussex, Kent and elsewhere - examples of which are now subject to the highest levels of conservation and heritage designation. Or, to the northern Portuguese fishing towns whose timber palheiros, endlessly rebuilt and with their long timber foundations reaching deep into the sand, resisted redevelopment along more conventional lines well into the twentieth century. All of these familial connections are subjects of drawings I have made in recent years, which aim to commemorate, memorialise and recall these structures and their quiet radicalism as they otherwise drift from view and social memory. I try to use a form of drawing that echoes, I hope, the simplicity, clarity and optimism of the original construction.

The game of ‘handmade house spotting’ is getting increasingly hard to play, the joy of finding new subjects for a drawing increasingly challenging. Examples of the type across the UK are frequently lost without ceremony, and without regular painting and maintenance, such lightweight timber structures decay rapidly: built by hand, they require regular attention by hand as well. In the intervening decades, ‘self-build’, when not acting under the radar against tremendous odds, has drifted into becoming a rich person’s game: Grand Designs culture, the granite worktop and the uPVC bi-folding door. This social and material drift gets perhaps to the heart of the significance of these structures beyond their architectural curiosity, to the core of why we need a more concerted and strategic effort to preserve them alongside other twentieth century structures. They are a tangible but shrinking reminder of one of the most significant and contentious transformations in the British landscape - a popular reclamation of rural and coastal beauty, undertaken by the working classes on their own terms, with their own hands, and with a renewable and low-impact material. A reclamation that has lessons to teach us in the present, and which echoes still in our culture, quieter each day.

Acknowledgements

This piece is indebted to social histories written by Dennis Hardy and Colin Ward, and by Ken Worpole, and to invaluable documentation made by Stefan Szczelkun, to the countless local amateur historians who have documented these places, and finally, somewhat perversely, to the narratives of writers and campaigners including Virgina Woolf, E. M. Forster, Clough Williams-Ellis and others who looked on the shanty with eloquent horror.

I explored the Russian dacha with Cristina Monteiro and Ishbel Mull in this essay for The Architectural Review, the Portuguese palheiro with Cristina Monteiro, the pageantry of Forster with Ruth Beale, and have written more or less constantly about Bungalow Town in Shoreham particularly here at The Spring Line but also here and here.